Mario Bava’s final years were characterized by several decidedly unusual projects, mostly in the realm of science fiction, which germinated after the ephemeral renaissance of Italian space operas – more than a decade after Antonio Margheriti’s “Gamma One” films of the mid-Sixties – caused by the phenomenal success of George Lucas’ Star Wars. The first, I cavalieri delle stelle / Star Riders, written by Luigi Cozzi, was supposed to be an Italian/US production with American International Pictures. According to Cozzi, Arkoff and Nicholson eventually settled for Cozzi’s own Starcrash due to the delays in the English translation of the script.[1] Anomalia, scripted by Dardano Sacchetti, was the intriguing story of a group of astronauts who end up on a planet at the far end of the universe, where a huge wall separates good from evil. Sacchetti’s story mixed space operas with darker, Lovecraftian tones (the wall features sculptures of horrible monsters which come to life) and was also supposed to be backed up by the Americans: Sacchetti claims he still has Roger Corman’s letter with the producer’s suggestions about the script.

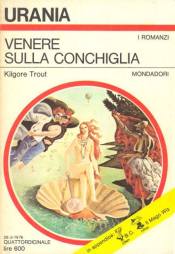

Then came the more curious project of the lot, Il vagabondo dello spazio (literally, “The Space Wanderer”), produced by Fulvio Lucisano’s Italian International Film. The story came from the novel Venus on the Half-Shell by Kilgore Trout, an alias for the American science fiction novelist Philip José Farmer (1918-2009).[2] Published in the U.S. in two parts in the December 1974 and January 1975 issues of “The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction”, Farmer’s novel came out in Italy with the title Venere sulla conchiglia, in the unmistakable white-and-red sleeve of the paperback series “Urania” (n. 93, March 28th, 1976), published fortnightly by Mondadori in newstands only, as the sci-fi counterpart to their popular “Giallo Mondadori” series. The novel was translated by Angela Campana and featured outstanding cover art by Karel Thole.

Such a choice is not surprising at all, given Bava’s fame as an omnivorous reader: besides, he had already taken inspiration from the Mondadori paperbacks for the unfortunate L’uomo e il bambino, which became Cani arrabbiati. And perhaps the book’s evocative title and the character it evoked – Bava filmed another “Venus” in his 1978 TV movie La Venere d’Ille, based on Prosper Mérimée’s book – did the rest. Nevertheless, Farmer’s novel was definitely bizzarre for Bava’s standards. How would he put it on screen? In his monumental volume Mario Bava—All the Colors of the Dark, Tim Lucas hypothizes that Il vagabondo dello spazio never went beyond the state of «a nebulous discussion»[3], pointing out that Farmer’s wife Bette never found any trace of the book’s rights being acquired by the Italians. This, however, wouldn’t have been an insurmountable problem, given the ways the Italian film industry operated at that time.[4] Proof that Il vagabondo dello spazio reached an embryonic pre-production state are the papers deposited at the Italian Ministry of Tourism and Spectacle on July 5th, 1978, which also reveal quite a few details about the film. Even though the rights were never bought, the document explicitly states the film being based on the «fantanovel “Venere nella [sic] conchiglia”».

To Bava, Il vagabondo dello spazio would mark the return to a genre he already dabbed with in the past with Terrore nello spazio (a.k.a. Planet of the Vampires, 1965), but which here is treated in an explicitly humorous manner. «The film», as the synopsis in the Ministerial papers state, «narrates the more or less comic adventures of Gaetano Simoncini through various planets: after the Earth turned into an immense lake due to a new flood, he took possession of a spaceship abandoned by extraterrestrials because the “freezer didn’t work” and the “toilet was defective”».

Definitely not the most inviting preamble, considering also Bava’s earlier forays into comedy. If the director’s sardonic vein is justly celebrated, especially when it’s paired with his taste for the macabre, his most explicitly humoristic films, such as Le spie vengono dal semifreddo (a.k.a. Dr. Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs, 1966), Quante volte… quella notte (a.k.a. Four Times That Night, 1969-72), and Roy Colt & Winchester Jack (1970) are generally considered among his lesser works. What in Heaven did Bava see in Farmer’s peculiar mixture of grotesque, drama, and assorted eccentrities? Venus on the Half-Shell moves seamlessly from dramatic scenes to Swiftian philosophical digressions and then to soft porn. However, we mustn’t forget that in 1973 Bava had written a short treatment, Porno Giove (“Porn Jupiter”), centered on a lewd reinterpretation of classic Greek myths, which swelled the ranks of the filmmaker’s unfinished projects in such a harsh decade for him as the Seventies were. Even more interesting is the fact that another of Bava’s temptative ideas was a film adaptation of none other than Jonathan Swift’s own Gulliver’s Travels.

As Lamberto Bava recalled, Porno Giove «was a film set in Ancient Rome, which among other things, featured phallophoric processions – with giant dicks, I mean…»[5] Bava’s six-page-long treatment – discovered in 2008 and summarized in «Nocturno Dossier» n. 70, May 2008 – opens with said procession: a young man is carrying a giant wooden phallus on his back, under the heavy summer sun. Once on the ground, the phallus becomes the bone of contention between three women, each of whom wants to use it as a memorial to delimit her piece of land. One woman curses Jupiter, and a priest looks preoccupied at the sky… Bava then cuts to the Gods, during a banquet in Olympus: Jupiter is bored and watched by the jealous Juno, Mercury tells lewd jokes, Venus lasciviously eyes Minerva and so on… Porno Giove tells the story of how Jupiter seduced Danae by turning into rain to reach the girl, who had been locked by her father inside a sealed chamber. The sequence, as described in the treatment, sounds amazing: «Drops of water slide on the sleeping girl’s chest and belly, on her thigs and crotch, and all slowly converge to one direction. The sleeping girl is enraptured by the beneficial rain, and eventually climaxes into orgasm». When Juno discovers her husband’s betrayal, she sets up a trial against him where Minerva acts as the prosecutor. During the trial, Jupiter’s many erotic feats, often involving metamorphoses, are recalled: he made love to Leda as a swan, seduced the nymph Callisto disguised as Artemis, and so on. Jupiter is found guilty, but he won’t accept the verdict, and retaliates by revealing the other gods’ secret erotic intrigues… Porno Giove ends with another phallophoric procession, at sunset, and Bava’s final words in the treatment are: «The story so briefly told will emphasize the simple and happy life of those ancient times where sex was not considered a sin and where the Gods themselves were not so dissimilar, by temper and passions, from human beings». All in all, it looks like a daring and inventive little film, in which eroticism is handled with much more convinction than in Quante volte… quella notte, and is emphasized by Bava’s attitude towards the fantastic: the sleeping Danae’s seduction scene looks like a rough draft of Daria Nicolodi’s astonishing erotic dream in Shock. Even more interesting is the emphasis on the juxtaposition between the Pagan and Catholic views of sex, possibly influenced by Pasolini’s “Trilogy of Life”.

But let’s return to Il vagabondo dello spazio. When mentioning, Bava scholars usually point out the name of Lucio Manlio Battistrada as the film’s scriptwriter: however, as Italian film historian Alberto Pezzotta points out[6], Battistrada himself, when asked about the film in 2004, didn’t recall anything about it, save for the fact that Bava passed him a copy of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (!). Battistrada’s name does not even appear in the papers deposited at the Ministry: the story and screenplay are credited to Italo Terzoli and Enrico Vaime, a popular duo of scriptwriters who had just worked on the central episode of the Fulvio Lucisano-produced omnibus comedy Io tigro, tu tigri, egli tigra (1978, Sergio Corbucci), starring Paolo Villaggio as a sci-fi novelist who’s abducted by aliens. Villaggio himself – then Italy’s most popular comic actor thanks to the success of his Fantozzi films[7] – was to play the lead Gaetano Simoncini, alongside Nadia Cassini (indicated in the papers as «1st planet girl», ), who also co-starred with Villaggio’s in Io tigro, tu tigri, egli tigra and Enrico Maria Salerno (Dokal the Magician). According to the papers, another key role, that of Chworktap, would be played by Saviana Scalfi, who had appeared in Sergio Corbucci’s Bluff – Storia di truffe e di imbroglioni (1976) and Luciano Salce’s Il… Belpaese (1977); however, the shooting schedule sheet mentions Giuliana Calandra (Deep Red’s Amanda Righetti) as Chworktap instead.

The tentative crew list goes as follows: the film’s composer and costume designer were not indicated, while the other names involved were Antonio Siciliano (editor), Egidio Valentini (production manager), Lamberto Palmieri (production supervisor), Lodovico Gasparini (assistant director), Annamaria Montanari (script girl), Gianfranco Mecacci (make-up artist) and Mario Dallimonti (sound technician). The d.o.p. as indicated in the notification of start of production is Roberto Gerardi, while the shooting schedule mentions Ennio Guarnieri instead.

As for the financial aspect, Il vagabondo dello spazio would benefit for a granted minimum of 800 million lire on the part of distributors, plus 400 million from foreign sales, amounting to a total budget of 1 billion and 200 million lire, while the shooting schedule contemplated a nine weeks’ shooting, from January 15 to March 11, 1979, at the Incir De Paolis studios in Rome (the exteriors are generally indicated as «Rome and surroundings»). A huge number of special optical effects were expected in order to create the various planets where the wanderer stops: Bava got in touch with Armando Valcauda, who had worked on Cozzi’s Scontri stellari oltre la terza dimensione a.k.a. Starcrash, 1978)[8]. To Lucisano, however, Il vagabondo dello spazio was also the occasion to recycle the costly spaceship set piece used in Io tigro, tu tigri, egli tigra. As for the film’s many alien creatures, in a passage from the interview included in the 1980 volume La città del cinema, Bava claimed that his intention was – incredible yet true – to leave them all offscreen.

«Last year I walked out of a film which was a Star Wars rip-off [Star Riders, perhaps? Authors’ Note]. In my opinion it would have taken one year and a half to finish it and we would never have it made the way the Americans did it. They had a crew of 60/70 people and spent 7 billions just in special effects. On the other hand, I suggested a comic science fiction film, from an incredible book of which I bought the rights, Il vagabondo delle stelle. The protagonist had to be Fantozzi who in the year 3000 goes from planet to planet, looking for the answer about where we come from. In the end there would be real monsters, which anyway the viewer must never see». [9]

Besides Bava’s enthusiasm and the misspelled title (“The Star Wanderer”), the allusion to the book’s rights that Bava claims to have bought is puzzling, given what Farmer’s wife stated. However, judging from the scant three-page story included with the notification of start of production, Terzoli and Vaime were indeed planning to reshape Venus on the Half-Shell and make it a vehicle for Paolo Villaggio’s comic antics. Such a procedure is evident by comparing the book’s opening with the first few lines of Terzoli and Vaime’s (unless it was Bava himself who penned it) synopsis.

Farmer describes the protagonist Simon Wagstaff as follows:

The Space Wanderer is an Earthman who never grows old. He wears Levis and a shabby gray sweater with brown leather elbow patches. On its front is a huge monogram: SW. He has a black patch over his left eye. He always carries an atomic-powered electrical banjo. He has three constant companions: a dog, an owl, and a female robot. He’s a sociable gentle creature who never refuses an autograph. His only fault, and it’s a terrible one, is that he asks questions no one can answer. At least, he did up to a thousand years ago, when he disappeared. […]

Oh, yes, he also suffers from an old wound in his posterior and thus can’t sit down long. Once, he was asked how it felt to be ageless.

He replied, “Immortality is a pain in the ass.”

Later on Farmer introduces Simon while he’s making love with his girlriend (atop the Gaza Sphinx!) and focuses on his physical aspect more thoroughly:

Simon was a short stocky man of thirty. He had thick curly chestnut hair, pointed ears, thick brown eyebrows, a long straight thin nose, and big brown eyes that looked ready to leak tears. He had thin lips and thick teeth which somehow became a beautiful combination when he smiled.

His alter-ego in Bava’s film, Gaetano Simoncini, is the umpteenth variation of Villaggio’s Fantozzi character: a mediocre office worker, single, who is preparing for a weekend in his cottage on the hills by feverishly polishing his car («a pathetic NSU Prinz»[10]) and who surrounds himself with such bad taste furnishings as an «obscenely ugly wood barometer from Val Gardena».

Here’s another important difference: whereas Farmer sets the story in a future Earth where humans cohabitate peacefully with extraterrestrials from the planet Arcturus («Arcturans looked so laughable when they sneered, twirling their long genitals as if they were key-chains») and ancient Egyptian monuments were restored – the reconstituted Sphinx bears the features of a famous movie star –, Il vagabondo dello spazio starts in a present-time and very recognizable Italy.

Just like in the novel, the story sets in motion when a huge flood submerges the planet. Farmer gets rid of it in less than a page, whereas the film synopsis dwells on it for over a third of its limited length: Bava was probably delighted with the idea of playing with special effects. What starts like an ordinary rainstorm quickly turns into a deluge: Rome is submerged, the city’s most famous monuments disappear beneath the waters, and (with a macabrely grotesque notation) the streets «are filled with floating corpses, all in their ridiculous clothes as they were dressing up for a trip to the beach or to the hills». The deluge sequence ends with an anticlerical sneer: St. Peter’s square in Vatican is flooded and we get to see the opening of the window in the Pope’s apartment «from which an atonal voice comes, which anyway doesn’t utter anything except for gurgling chanting. In the square the cardinals are floating in their red robes».

Simoncini picks up his car and his banjo (the banjo was a vital element in the novel, which here sounds rather awkward, given the Mediterranean setting: why not a guitar or a mandolin instead?), which he loves to play, much for the chagrin of his domestic animal. Then the story moves on to a few more apocalyptic vignettes, such as a train of excursionists being swallowed by the flood, or the raising waters behind the car of the unaware Simoncini, who is driving on a steep climb to his little cottage. Where Gaetano finally realizes he is completely surrounded with water, a note warns that from now on the story «is grafted into that of Venus on the Half-Shell, with variations due to the more “Latin” characters of the protagonist as well as the choices determined by the film’s length». The synopsis then proceeds in a much more concise way, with occasional notations which hint at the possibility that a script hadn’t actually been written yet.

As in Farmer’s novel, an unexpected haven for the Wanderer comes in the form of a spaceship, which in the book is not alien but Chinese, with the sign “Hwang Ho” on the side. Simoncini climbs up on the ship which comes floating right under his nose, «swinging on the water like a boat»: he fortuitously manages to operate the controls and then embarks on a philosophical-existential conversation with the ship’s intelligent computer (a sort of female version of 2001’s HAL-9000, which falls in love with Simoncini: a twist nowhere to be found in the book).

Bava’s story eliminates all the Biblical implications (in the book, Simon arrives with his “ark” on the top of Mount Ararat: there he meets the hundred-year-old Comberbacke, who tells him the deluge was caused by the alien race of the Hoonhors, «the race that’s been cleaning up the universe»). As Bava had stated, his intention was to rework in a comical way Simon’s decision to leave Earth and «start asking the primal question. Why are we created only to suffer and die?», which gives way to the Wanderer’s peregrination in space.

The rest of Il vagabondo dello spazio follows Simoncini’s landings on various planets, in a way that sounds (at least superficially) faithful to Farmer’s description. Perhaps, to Bava, it was also an opportunity to reconnect to a classic of children’s literature such as Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, which has a similar rhapsodic structure as Farmer’s novel, describing the titular prince’s wanderings from one planet to another. However, Saint-Exupéry would never have indulged in Farmer’s bewildering divagations, often halfway between mockery and pornography, with their detailed descriptions of the extravagant – and often hilarious – couplings of alien races of different forms, shapes and sexual attitudes.[11]

Sometimes, though, Bava’s synopsis reshuffles the cards, taking elements from the novel and putting them in a different context. The first planet Simoncini visits is inhabited by «weird beings who playfully cover their faces while they leave their genitals exposed, which they shake wildly into the air to express happiness and satisfaction»: these are the Arturans as descripted by Farmer in the opening pages of Venus on the Half-Shell. In the film, this would lead to a sight gag involving Gaetano’s dog, who, «willing to play and intrigued by those swirling balls, comes back to Gaetano holding in the mouth the alien leader’s genitals». To appease the latter’s wrath, Simoncini builds him a prothesis of sorts by using a pinwheel: another gag absent in the book. He then meets a baseball maniac (old Comberbacke, who in the novel appeared on the mount Ararat) and reaches a high tower (as Farmer writes, «this tower was about a mile wide at its base and two miles high. It was shaped like a candy heart, its point stuck in the ground») over which he writes a stupid tourist phrase, making it collapse.[12]

And this is perhaps the measure of the difference between Il vagabondo dello spazio and Venus on the Half-Shell. The sight gag of the collapsing tower is an invention by Terzoli and Vaime (or the author of the synopsis): a moment very much in the vein of Villaggio’s Fantozzi films, which demands laughter by ironizing on the Wanderer’s awkward behavior. In the book, Simon lands upon the monumental building, the relic of an alien – or perhaps divine – civilization close to Kubrick’s monolith («It had been there for about a billion years, long before the human population had evolved from apes or even from shrew-sized insect eaters. Perhaps it had even been erected before life had crawled out of the primeval seas») and vainly looks for an entrance. Later on, upon returning to the ship, he notices that the “Hwang Ho” has sunk into the soft guano that covers the tower’s peak, and he must dig his way with his bare hands. «Two hours later, dirty, sweaty, and disgruntled, he broke through and fell into the port. It took a half-hour to clear out the port entrance and another half-hour to clean up himself and the pets. His usual good spirits returned shortly afterward. He had told himself that he shouldn’t get angry at such a little thing. After all, a man should expect to get his hands dirty if he dug into fundamental issues». Farmer surprisingly – and seamlessly – turns a crass gag into a philosophical metaphor, not the less pertinent for that. No wonder many critics at that time thought that Kilgore Trout was actually Vonnegut.

The second planet, Shaltoon, is inhabited by hypersexuated feline creatures, whom Farmer/Trout describes as follows:

The people that poured out of the building were human-looking except for pointed ears, yellow eyes which had pupils like a cat’s, and sharp-pointed teeth. […] They were all in the mating season, which lasted the year around. Their main subject of conversation was sex, but even with this subject they couldn’t sustain much talk. After a half-hour or so, they’d get fidgety and then excuse themselves.

To Farmer, the Shaltoonians’ sex-addiction – they don’t know the word “love”, live more or less like the Terrestrials, if it weren’t for the low amount of suicides, since «instead of getting depressed, they went out and got laid» – is the pretext for a satyrical sting in the tail: «Earthmen were dedicated to getting to the top of the heap, whereas the Shaltoonians devoted themselves to getting on top of each other.» A bitter remark on the part of an intellectual who had experienced first-hand the sunset of the Age of Aquarium, and who always gave ample room to the theme of sexual freedom in his work (think of his controversial novels The Lovers, 1961, and A Feast Unknown, 1969). It’s highly unlikely that any of this would be found in Bava’s version – besides a few curvaceous extras in skin-colored leotards, that is.

The Shaltoonians are subjects of the cat-queen Margaret: on paper, this looks like an ideal role for the ravishing Nadia Cassini (perhaps erroneously credited as «1st planet girl» in the Ministry papers?), in the (scant) clothes of the sensuous sovereign who seduces and weakens the Wanderer during a torrid night of love («Her high, firm, uncowled bosom was proud and rosy. Her hips and thighs were like an inviting lyre of pure alabaster. They shone so whitely that they might have had a light inside» as Farmer writes) and gives him a potion of immortality.

«There is much that can be kept from this part», as the film’s synopsis comments, «except for the barrels where [they] throw the murdered infants and the bit about the ancestor rotation». If it weren’t already patent, such a comment emphasizes the intention of watering down Venus on the Half-Shell’s most dramatic or controversial passages, such as the cat-men’s atrocious pro-life practice of drowning their newborn babies: «an aborted baby didn’t have a soul. But a baby that made it to the open air was outfitted with a soul at the moment of birth. If it died even a few seconds later, it still went to heaven», as Farmer writes – an impossible thing to put on screen in 1979’s Italy, where a controversial law on abortion (l. 194/1978) had just passed, leading to a furious ideological battle on the part of the Catholic world. Same for one of the book’s weirdest ideas: «the body of every Shaltoonian contains cells which carry the memories of a particular ancestor. The earliest ancestors are in the anal tissue. The latest are in the brain tissue […] anyway, when a person reaches puberty, he must then give each ancestor a day for himself or herself. The ancestor comes into full possession of the carrier’s body and consciousness.» This provides Farmer with the starting point for a digression on a society rigidly divided into classes, where membership is perpetuated from generation to generation, and an exponential multiplication of witty socio-political paradoxes.

From here onwards, the synopsis of Bava’s project is just a series of concise notations: half a page of very vague indications with passing references to the book. There are indeed a few scatological inventions taken from the novel, as the «zeppelin-creatures» with humanoid faces who drive themselves in the air with giant maleodorant farts, in the next planet that Simon/Simoncini visits. Once again, though, the additions to Farmer’s ideas are banal. Venus on the Half-Shell describes these creatures’ male-dominated society, where the females are exploited by their partners («We’re just objects to them – said one female. – Nutrition and pleasure objects»), and has the Wanderer’s intervention break the society’s delicate equilibrium. In Bava’s version, more prosaically, Simoncini takes advantage of the aliens’ farts to set up «a big concert with a choir of rasberries accompanying his songs». Not exactly something to write home about…

At this point in the novel, Farmer introduces the character of Chworktap (anagram of Patchwork), whom the Wanderer sees as she rises from the foam of a wave like in Botticelli’s painting Birth of Venus. «She wasn’t standing on a giant clamshell and there wasn’t any maiden ready to throw a blanket over her», as Farmer writes, «but the shoreline and the trees and the flowers floating in the air behind her did resemble those in the painting. The woman herself, as she waded out of the sea to stand nude before him, also had hair the same length and color as Botticelli’s Venus. She was, however, much better looking and had a better body – from Simon’s viewpoint, anyway. She did not have one hand covering her breast and the ends of her hair hiding her pubes».

As the name suggests, Chworktap is the ideal female from a male’s perspective: beautiful, uninhibited, fun, a great cook, and always ready to satisfy her partner’s desires: a Girl Friday who brings to mind Montana Wildhack, the porn actress secluded with Billy Pilgrim in the Tralfamadorians’ intergalactic zoo in Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse-Five. But as Simon discovers after their first memorable lovemaking session, Chworktap is something more than a woman:

«I hope you’re not pregnant, Chworktap. I don’t have any contraceptives, and I didn’t think to ask you if you had any.»

«I can’t get pregnant.»

«I’m sorry to hear that,» he said. «Do you want children? You can always adopt one, you know.»

«I don’t have any mother love.»

Simon was puzzled. He said, «How do you know that?»

«I wasn’t programmed for mother love. I’m a robot.»

Only two years earlier, Fellini had ended his Casanova (1976) with the icy sequence of the titular character dancing with a mechanical doll. Less than a couple of years later, Alberto Sordi would direct and star in Io e Caterina (1980) also produced by Lucisano, an adult fable where the average man’s sex fantasies come to life in the story of the businessman who has a company build a female robot for his pleasure. In the meantime, Italian streets were filled with feminists chanting: «Tremate, tremate, le streghe son tornate!» (“Tremble, tremble, the witches are back!”). In a sense, the natural evolution of a book so closely related to the present, such as Venus on the Half-Shell was, could have been that of a socio-philosophical fable.

However, the character of the artificial woman also recalls one of Bava’s favorite themes, the play between the animate and the inanimate as seen in films such as Lisa e il diavolo (a.k.a. Lisa and the Devil, 1973). If we had to stick to a strictly authorial and dogmatic conception of Bava’s oeuvre, the character of Chworktap would be the ideal cue: however, it’s highly unlikely that either the director or his scriptwriters cared much about all this. Casting Scalfi or Calandra for the role would have the effect of underplaying the character’s erotic potential: the synopsis specifies that the love story between her and Simoncini «can substantially remain the same as in the novel», although «somewhat changed according to his personality». Which makes one gather that, similarly to other films where Villaggio played a comically unlikely Alpha male – such as Sergio Corbucci’s Robinson Crusoe parody Il signor Robinson, mostruosa storia d’amore e d’avventura (1976), co-starring Janet Agren (who would have made for an outstanding Venus, by the way) –, the love affair with the girl was destined to accommodate comic elements.

The synopsis then dramatically shortens the book, leaving out the chapter on planet Lalorlong, whose inhabitants look like «automobile wheels with balloon tires», which is quite downbeat despite the premises: «Look at how poverty-stricken, how bare, this planet is. […] So, if there’s little outside to see, there’s little to think about inside.».

Then it’s the turn of the planet where – as the synopsis laconically synthesizes – the tail transplant and the visit to the cannibal magician (Enrico Maria Salerno), who tries to eat the Wanderer, take place. The papers indicate Salerno’s character as Dokal, which in the novel is the name of the planet, inhabited by natives very similar to humans «except for one thing. They had long prehensile tails. These were six to seven feet long and hairless from root to tip, which exploded in a long silky tuft». Simon is immediately taken by the natives and brought to a hospital, where a tail is transplanted into his body: without it, he would look repugnant to the aliens. It is logical to imagine that Bava envisioned a comical rewriting “Fantozzi-style”, whereas Farmer opts for a bizarre description of the weird uses (even erotic…) of said appendices, as Simon is called on to satisfy a couple of local girls.

The encounter with the magician (called Mofeislop in the novel), at whose palace Simon arrives exhausted and hungry after climbing a high mountain, is the opportunity for the novel’s most straightforward horrific segment, and one that would offer Bava the chance to dwell into territories closer to his favorite themes. Let’s envisage the magician’s abode («Three stories high, thirteen- sided, many-balconied, many-cupolaed, it was built of black granite»), recreated by Bava’s skills through maquettes, colored lights and so on; the huge door, made of oak and with a «monstruously large and rusty lock», which opens creaking «as if Dracula’s butler was on the other side»; the magician’s fetid servant Odiomzwak, who looks like «Doctor Frankenstein’s assistant or perhaps Lon Chaney senior in “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”». A mixture of Gothic clichés served with a tongue-in-cheek bravado: an ideal playing field for the Sanremese maestro.

And let’s picture Enrico Maria Salerno as the gloomy magician: «a tall thin man, all forehead and nose, warming his hands and tail. He was dressed in furry slippers, bearskin trousers, and a long flowing robe printed with calipers, compasses, telescopes, microscopes, surgeon’s knives, test tubes, and question marks». Then let’s imagine the meeting taking place just like one of those between Fantozzi and his employer, without Farmer’s philosophical mumblings – which range from Frankenstein to Christ and Pilate, passing through Oedipus and the Sphinx.

Treated as a guest, since the magician has promised to tell him all the answers he’s looking for, Simon eats and eats, and the magician checks his weight every morning (an opposite situation to a sequence in 1980’s Fantozzi contro tutti, where Fantozzi is undergoing a slimming treatment in a private clinic run by the Nazi-like prof. Birkermaier). Eventually, Simon discovers that he is being fattened up: the sage devours all the visitors who periodically climb the mountain looking for the Truth. On paper, the episode is the closest to Bava’s taste for the macabre: the Wanderer is tied to a chair, while Mofeislop’s assistant sharpens the knives to gut him, and the sage quibbles about the taste of his victims’ flesh («I hope you’re not a filthy atheist […]. I’ve eaten too many of them, and they’ve all had a rank taste that is unpleasant»). The magician also gives Simon the answer to the ultimate questions:

«It’s this. The Creator has created this world solely to provide Himself with a show, to entertain Himself. Otherwise, He’d find eternity boring.

“And He gets as much enjoyment from watching pain, suffering, and murder as He does from love. Perhaps more, since there is so much more hate and greed and murder than there is of love. […]

«That’s it?» Simon said.

«That’s it.»

«That’s nothing new!» Simon said. «I’ve read a hundred books which say the same thing! Where’s the logic, the wisdom, in that?»

«Once you’ve admitted the premise that there is a Creator, no intelligent person can come to any other conclusion.»

The magician’s words perfectly fit to the grotesque and cruel humanity as portrayed in Bava’s main works of the decade, namely Reazione a catena (a.k.a. Bay of Blood, 1971), and Cani arrabbiati, not forgetting 5 bambole per la luna d’agosto (a.k.a. 5 Dolls for an August Moon, 1970). They make the perfect counterpart to the filmmaker’s «dark and disconsolate» view of the world where, according to Alberto Pezzotta, «Bava pairs explicit evil and the evil that’s hidden behind the façade of banality» [13]. The sci-fi context here would have allowed the director to follow his apocaliptic vein, which in his earlier films was limited to a defined microcosm: perhaps – despite Villaggio’s presence, the many comic and surreal digressions, and so on – what really hit Bava about Farmer’s novel was the chance to put into film (let’s not forget the opening scenes, with those red bodies floating in St. Peter’s square – just like the fly in the bay waters in Reazione a catena) a sense of repulsion for a stupid and cruel humanity, multiplied and expanded to contain the entire universe.

These are only hypotheses, of course. Ruminations on a film that never went beyond pre-production stage.

The fight with the magician and his axe-wielding assistant, in which Simon receives unexpected help from his dog, allows for more horrific details: Simon’s domestic owl Athena eats and swallows the Wanderer’s left eye, gouged out by Odiomzwak (does that sound like a déjà-vu? Think of Argento’s Opera), and the magician cuts off Simon’s tail with the axe (hence the Wanderer’s inability to be sitting for a long time…). It ends with Simon saved at the very last minute by Chworktap’s intervention, while the sage dies with his throat ripped open by the dog’s fangs. Would Bava retain the novel’s most gruesome details? The film’s comic tone would seem to exclude it, yet Bava’s following unfilmed sci-fi project Star Express would mix splatter and comedy with unusual ease.

The synopsis for the film leaves out Simon’s visits to other absurd planets described in the novel: Goolgeas, whose inhabitants have funnel-shaped ears and are completely hairless, except for bushy eyebrows, and believe they can see God’s face through alcohol and drugs; and Shonk, where the natives go naked except for their faces, which are covered by masks («since genitals didn’t differ much in size or shapes, and couldn’t be used to distinguish one person from another, the Shonks regarded the face as their private parts. The Shonks reserved the glory of their private parts for the eyes of their spouses alone»).

The fifth and last planet where Bava’s Wanderer lands is inhabited by intelligent roosters and hens. Farmer described them as cockroaches as huge as elephants, but the substance is left the same. The Wanderer has come to the last leg of his trip: planet Clerun-Gowph, home of the creatures who had built the gigantic monolith-towers, billions of years earlier. «It’s on their planet that God sojourned – that is, “It” (the egg is pure form, perfection, mystery […])», as Bava’s synopsis points out: the change from insects to hens is not casual. «“It” now is not anymore, yet on the planet there still lives (as in Venus on the Half-Shell) Bingo, a capon of great wisdom who will be Simoncini’s last encounter».

Bingo – in the novel an old and hoary cockroach crouching on a mass of rugs near a framed photograph of a blue cloud with a dedication by “It” – delivers a monologue which offers Farmer the pretext for developing a weird cosmogony: life on the other planets was born and developed from garbage and excrements dumped by the Clerun-Gowph in the soupy primeval seas near the towers.

Simon was shaken. He was the end of a process that had started with cockroach crap.

«That’s as good a way to originate as any,» Bingo said, as if he had read Simon’s thoughts.

But there is more. Through a gigantic computer, which for billions of years the aliens have fed with data, the Clerun-Gowph have all the answers at their disposal, because «once the universe is set up in a particular structure, everything from then on proceeds predictably. It’s like rolling a bowling ball down the return trough. […] What seems Chance is merely ignorance on the part of the beholder. If he knew enough, he’d see that things could not have happened otherwise».

Yet, as Bingo notes, it’s better to stay ignorant, because «it’s no fun knowing everything». The old insect, who once knew the origin of “It” and forgot, sums it up like this:

«There is no such thing as an afterlife. That I know. That is one thing I remember It telling me.»

He paused and said, «I think.»

«But why, then, did It create us!» Simon cried. […] «Didn’t It know what agony and sorrow It would cause sextillions upon sextillions of living beings to suffer? All for nothing?»

«Yes,» Bingo said.

«But why?» Simon Wagstaff shouted. «Why? Why? Why?»

Old Bingo drank a glass of beer, belched, and spoke.

«Why not?»

Perhaps, after all, Bava was just interested in getting to this ending. Why not? Bingo’s laconic non-response is the ideal punchline to a deterministic universe founded on repetition – as in Operazione paura (a.k.a. Kill Baby, Kill, 1966) and Lisa e il diavolo – as the fundamental pattern of existence, and on pain and death as the only constant.

Eventually Bava abandoned Il vagabondo dello spazio. In his book Pascal Martinet[14] suggests that the director was not convinced about the comic elements, which is highly unlikely considering Bava’s aforementioned interview in the La città del cinema volume, where he expressed his enthusiasm about an idea of a Fantozzi in Outer Space kind of movie. Perhaps the project just didn’t look too promising from a commercial point of view: would Villaggio fans really sit through such a weirdo? Or perhaps it was Lucisano who wasn’t convinced at all about the film? It might as well be that eventually there were problems with obtaining the film’s rights, after all… However, Bava would reprise quite a few elements in Star Express, written by himself and Massimo De Rita and produced by Italo Zingarelli and Massimo Palaggi, which he was supposed to start filming in May 1980.

What is left of the latter film are a pair of treatments, 67 and 55 pages long: as Alberto Pezzotta explains in an essay about the film[15], the main difference between them is the ending (which is more elaborate in the second one, and, as Pezzotta comments, more similar to a children-oriented TV movie); there are also indications of the cuts to be made to ensure a “lighter” TV version. Sign o’ the times.

The debts to Il vagabondo nello spazio are patent. First of all, Bava reprises the main character of the Wanderer (who in Star Express becomes a young pacifist hippie named Vagabond), and then the themes of an apocalypse which destroyed Earth and an intergalactic journey in a battered spaceship/ark, up to the character of the demiurge or would-be such who wants to control the fate of the universe. Bava seemingly cared much more about Star Express, according to his son Lamberto: he had already drawn sketches and storyboards. «It was set in a future where everything was falling apart, and for instance the space bases were represented just like the staging post stations in Westerns, with a strong wind seeping away the sand, the faded signs oscillating and creaking in the wind [remember Sei donne per l’assassino, a.k.a. Blood and Black Lace? Authors’ Note]… a universe where everything was in ruins, with beggars everywhere… yes, it was full of ragamuffins and homeless people, with just a few spaceships still flying, because no one knew how to fix them anymore» as Lamberto Bava’s recounted.[16]

However, Star Express was definitely a mixed bag, as can be easily detected from the plot and characters, an assorted weird bunch with unlikely names to say the least, all traveling on a ship’s last voyage to Earth: a saloon maitresse, Ma’ Peripat, and her “girls”; an old interstellar sheriff called Le Carré (Bava’s homage to the author of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy); an elderly thief by the name of Old-Scass-Cazz (a heavy pun on “scassacazzo”, a very vulgar Italian way of saying “pain in the ass”); a neurotic scientist, Nevron, who’s carrying friendly alien amoeba specimens; a mother and her alien baby child; the aforementioned Vagabond; a typical western hero, Old Moses, and his two sex-hungry sons.

Despite the evocative setting, according to Pezzotta the story soon turns into a mixture between Alien and 5 bambole per la luna d’agosto, and Lamberto Bava himself called it «a sort of outer space version of Agatha Christie’s classic whodunit And Then there Were None»). In fact, after a carbonized corpse is found with a sphere attached to it, things get definitely grim: the sphere contains a mysterious substance, a form of energy which can either destroy the universe or save the Earth from dying, but soon somebody starts killing the spaceship’s crew one by one, in gruesome ways. The main suspect is the alien child, who goes around playing with… a ball, Operazione paura-style, but in the end the culprit turns out to be the ship’s Captain – a megalomaniac who wants to be God and decide the future of the universe.

As the synopsis makes it evident, Star Express was definitely more inclined towards giallo and horror, with splatter elements that uneasily rub shoulders with comical moments and foul language aplenty. In one scene, one of Moses’ sons is threatened to be castrated in the same way as Ninetto Davoli in an episode of Pasolini’s Il fiore delle Mille e una notte (a.k.a. Arabian Nights, 1974), but this eventually turns out to be just a life lesson from his father, who explains: «This was to make you understand that all the fucking you could get would be nothing compared to the ass-fucking you would eventually suffer.» A line that would not have been out of place in a poliziottesco or a Western. Speaking of which, Bava and De Rita copiously drew from Spaghetti Westerns: the film would end with a Sergio Leone-inspired duel between the Captain and Vagabond, with the latter uttering the words: «When an armed man meets an unarmed man, the armed man has already lost». Clint Eastwood’s character wouldn’t have agreed. Yet, as Pezzotta underlines, there are several scenes worthy of Bava’s genius. Example? Before dying, an old man rips the flesh off his arm and plays a melody by using his own tendons as if they were a violin’s strings. That is the very same nightmare Bava recounted to Ornella Volta in a 1972 interview published on the French magazine «Positif».[17]

Star Express was an even more difficult (and costly) project, compared to Il vagabondo dello spazio, and probably doomed to mediocre results, judging from the elements we have. Yet, it’s a further indication that most likely, after the unsustainable reality of Bava’s masterpiece Cani arrabbiati and the unveiling of the mediocrity of everyday life underneath the trappings of a ghost story in Shock (1977), and at the turn of a decade which would mark the death of Italian popular cinema, to Bava science fiction was a last resort. To keep dreaming a cinema of wonders, yet to be explored without rest. Just like the Wanderer would do.

NOTES:

[1] Alberto Pezzotta, Altri spazi – Progetti Sci-Fi, in Manlio Gomarasca, Davide Pulici, Genealogia del delitto. Il cinema di Mario e Lamberto Bava, «Nocturno Dossier» n. 24, July 2004, p. 21.

[2] The origin of Farmer’s pseudonym – Kilgore Trout is a character featured in several novels by Kurt Vonnegut jr. – and the ensuing querelle between the two writers would make for an essay on its own: suffice to say that Farmer asked his colleague permission, which Vonnegut would later bitterly regret, as many reviewers believed the novel to be the work of Vonnegut himself, hiding behind a transparent alias in order to deal with more freedom about scabrous issues. With understandable chagrin on the part of the author of Slaughterhouse-Five. Trout, a penniless sci-fi writer who’s forced to publish his storis in porn magazines, appears for the first rime as a marginal character in God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1963) quindi in Slaughterhouse-Five (1969); he’s the main character in Breakfast of Champions (1973), pops up again in Jailbird (1979), and even in a weird form in Galápagos: A Novel (1985, where he’s a spirit from the beyond) and, again as the main character, in Timequake (1997). Farmer, who planned another novel with the alias Kilgore Trour, never used the pseudonym again after the argument with his colleague.

[3] Tim Lucas, Mario Bava – All the Colors of the Dark, Video Watchdog, Cincinnati OH 2007, p. 999.

[4] Paolo Villaggio himself later starred in no less than two movies liberally “inspired” by Hollywood classics: Fracchia la belva umana (1981, Neri Parenti), which reprised the plot of John Ford’s The Whole Town’s Talking (1935), and Sogni mostruosamente proibiti (1982, Neri Parenti), a remake of sorts of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (which came out in Italy as Sogni proibiti…).

[5] «Nocturno Dossier» n. 24, July 2004. A similarly bawdy retelling of ancient mythology can be found in a recently published unfilmed treatment attributed to Fellini, L’Olimpo, apparently to be developed into a TV series. The book has caused some controversy among scholars: the style and the content (with ample room for explicit sex) don’t seem the work of Fellini, and some have suggested that L’Olimpo was actually penned, at least partially, by his collaborators, namely the prolific Brunello Rondi, after his friend’s suggestion. See Gianfranco Angelucci, Su quell’“Olimpo” erotico c’è solo l’ombra di Fellini, «Il Giornale», April 15, 2017.

[6] Alberto Pezzotta, Mario Bava (III edition), Il Castoro cinema, Milano 2013, p. 129.

[7] Fantozzi debuted on screen in the eponymous 1975 film directed by Luciano Salce (also known as White Collar Blues). Villaggio played the same character in nine sequels, the last being 1999’s Fantozzi 2000 – La clonazione.

[8] Lucas quotes Valcauda’s words about the project. Valcauda knew Bava on the set of another omnibus comedy produced by Lucisano, Tre tigri contro tre tigri (1977, Steno, Sergio Corbucci) where the former took care of special optical effects. Valcauda recalls that Corbucci, Lucisano and editor Amedeo Salfa where not satisfied of Valcauda’s work (most likely in the film’s third episode, again starring Paolo Villaggio). «Mi ricordai dell’amicizia di Lucisano con Bava, e chiesi che il mio lavoro venisse giudicato da lui. Se anche Bava fosse stato d’accordo che era necessario, l’avrei rifatto completamente. Mario venne, guardò il materiale, fece un piccolo applauso e suggerì solo un miglioramento. Gli altri stavano seduti lì, verdi di rabbia”». Lucas, p. 999, from Valcauda’s letter to Lucas dated 27 April 1990.

[9] Assessorato alla cultura del Comune di Roma, La città del cinema – Lavoro e produzione nel cinema italiano 1930/1970, Napoleone, Roma 1979, pp. 88.

[10] Prinz’s owners were considered losers par excellence back then in Italy, NSU Prinz being a very low-priced, ugly car. Fantozzi drove a Prinz too…

[11] The Swiftian philosophical subtext of Venus on the Half-Shell is also evident in one of the book’s characters, whom Farmer would later re-use in several short stories for “The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction”: one Jonathan Swift Somers III, introduced in the novel trough his gravestone, à la Spoon River Anthology, and whose works are often quoted by Simon in a chinese box construction which is typical of a hypernovel, in the sense introduced by Italo Calvino.

[12] The gag was perhaps inspired by another passage in the book. Where he lands on planet Lalorlong, Simon sees one of the gigantic towers crumbled on the ground: «The tower must have been erected a billion years ago and fallen many millions ago. What a sound its topple must have made!» .

[13] Alberto Pezzotta, Mario Bava (III edition), Il Castoro cinema, Milan 2013, p. 122.

[14] Pascal Martinet, Mario Bava, Edilig, Paris 1984, p. 19.

[15] Alberto Pezzotta, L’ultimo viaggio spaziale, in Manlio Gomarasca, Davide Pulici (edited by), Genealogia del delitto. Il cinema di Mario e Lamberto Bava, «Nocturno Dossier» n. 24, July 2004, p. 21

[16] In reporting Lamberto Bava’s statements to Luigi Cozzi, included in Cozzi’s book Mario Bava – I mille volti della paura (Profondo Rosso, Rome 2001, p. 155), Lucas confuses Il vagabondo dello spazio and Star Express and pegs away in trying to understand why Bava wanted to turn Farmer’s novel into a whodunit: «Though the setting of the film sounds promising, the prospect of reducing Farmer’s flamboyant satire to yet another variation of Ten Little Indians, with the myriad of life forms of the novel kept offscreen, makes one vaguely grateful that the picture wasn’t made» (Lucas, Mario Bava cit., p. 999). Therefore, Lamberto Bava’s reference to his father having prepared sketches and storyboards must also be referred to Star Express and not to Il vagabondo dello spazio.

[17] Ornella Volta, Entretien avec Mario Bava, «Positif» n. 138, 1972.

(with special thanks to Mark Thompson Ashworth)